| Format (medium) |

| Beta SP, PAL, 4:3, colour (colour), stereo |

|

|

| Entstehungsjahr (year of production) |

|

|

| Entstehungsland (country of production) |

|

|

| Mitwirkende/Partner (assistent/partners) |

| Michael Jung, Nicole Six, Dariusz Kowalski, Sasha Pirker, Emanuel Danesch, Martin Siewert (sound mastering), Matthias Hammer (cast/welder), Michaela Schwentner, Evamaria Trischak |

|

|

| Unterstützt durch (supported by) |

|

|

| Signatur/Dating/Bezeichnung (signature/dating/designation) |

|

|

| Standort (location) |

| Österreich, Wien (Austria, Vienna) |

|

|

| Ausstellungen (exhibitions) |

| • CINEPLEX. Experimantalfilm aus Österreich, Secession, Wien/Vienna, A 2009 • Prelude*), Hafen2 | interim.projekte, Offenbach am Main, D 2010 |

|

|

| Festivals (festivals) |

| • Diagonale - Festival des österr. Films, Graz, A 2009 |

|

|

| Literaturnachweis (reviews) |

| Secession (Hg.), Cineplex, Experimentalfilme aus Österreich, Secession, Wien 2009 • artmagazine.cc (Online-ed.), Roland Schöny: Im Projektionsraum der Neuen Filmkunst, 2009 |

|

|

| Schlagworte (keywords) |

| Experimentalvideo (experimental video) |

|

|

| Lizenzvertrag/Archiv (licence contract/archive) |

|

|

| Verkauf/Vergabe 1 (selling/disposal 1) |

|

|

| Verkauf/Vergabe 2 (selling/disposal 2) |

|

|

| Verkauf/Vergabe 3 (selling/disposal 3) |

|

|

| Verkauf/Vergabe 4 (selling/disposal 4) |

|

|

| Verkauf/Vergabe 5 (selling/disposal 5) |

|

|

| Beschreibung - D (description german) |

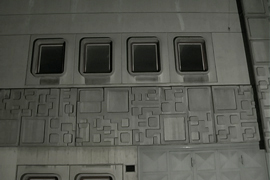

| Eigentlich gibt es von Annja Krautgassers (alias [n:ja]) jüngstem Video zwei Versionen: Eine trägt den Titel Innerer Monolog, die andere heißt Beyond. Obwohl sie für beide Arbeiten, bis auf die Schlussszene, annähernd das gleiche Bildmaterial verwendet,

ist der Unterschied letztlich doch gravierend. Während sie in Innerer Monolog stark auf das Architekturporträt eines Gebäudes im 15. Wiener Gemeindebezirk fokussiert, welches sie über die Tonspur mit imaginären Geschichten atmosphärisch anreichert, erweitert Beyond die Blickweise um eine weitere Ebene. Die Künstlerin zeigt in der letzten Einstellung das (unerwartet große) Filmset und dekuvriert damit die Machart des Videos. Die sichtbaren Produktionsbedingungen setzt sie dabei genau gleich in Szene wie davor die einzelnen Versatzstücke der architektonischen Komposition. Lediglich das grell in unterschiedlicher Stärke aufblitzende Licht, das durch einen Schweißvorgang erzeugt wird, öffnet und schließt die Sicht auf die Häuserfassade, aber auch auf die aufzeichnende mediale Apparatur. Die Architektur – stimmigerweise ein Umspannwerk – flackert im Rhythmus des Arbeits-vorganges. Das Video entpuppt sich als strukturell gebautes Architekturporträt und „Making-of“ zugleich.

Formal besteht Beyond aus drei ineinanderfließenden Bewegungen, die immer wieder durch Schwarzbilder – die komplette Dunkelheit – unterbrochen sind. Zuerst gleitet die Kamera nach rechts über einzelne Details der modernistisch anmutenden Häuserfront, bevor der sich weitende Blick auf die Fassade – in Folge mehrfach, aber dennoch fragmentarisch bleibend – freigegeben wird. Knapp ab der Hälfte der Arbeit dreht sich die Kamerabewegung um, bis das Bild von der Gebäudefront mit einem leicht nach oben ziehenden Schwenk in der Dunkelheit der Nacht versinkt. Dabei betreibt Krautgasser auch ein Spiel mit Genrekonventionen. Ganz der Suspense-Logik folgend, ist immer nur ein Teil oder eine Spur zu wenig zu sehen, während auf der Tonebene – vorbeiziehende Autos, klappernde Stöckelschuhe, Vogelgezwitscher – alles nur angedeutet bleibt. In der offiziellen Architekturgeschichte taucht dieses Gebäude übrigens bis dato nicht auf. Das in den 1970er Jahren vom Architekten Heinrich Schmid gebaute Werk existiert ähnlich wie in Beyond vorwiegend im Verborgenen.

(Dietmar Schwärzler)

Sicheres Navigieren

Ortsbezug und Raum in den Arbeiten von Annja Krautgasser

Martin Fritz

KünstlerInnen müssen Beziehungen zu den Orten ihrer Arbeit entwickeln. Ob im Studio,

auf Reisen oder im Inneren der Institutionen: Es stellt sich die Frage nach dem Verhältnis

des Kunstwerks zum Ort seiner Entstehung. Dieses Verhältnis schien durch die vielfältigen Ablösungen der Kunst von der Abbildung ihrer Umgebung irrelevant geworden zu sein, bis es spätestens seit den 1960er Jahren als formaler Anspruch der Site Specificity und als

soziales Potenzial der Kontextorientierung aktualisiert wurde. Zusätzliche Brisanz entwickelte die Fragestellung im Zusammenhang mit jener Mobilität, die das Kunstgeschehen seinen Beteiligten abfordert, bzw. jener geografisch-räumlichen Beweglichkeit, die es ihnen ermöglicht, multiperspektivisch zu agieren. Vielfältige Residencies, an Reisen gebundene Arbeitsstipendien und transnationale Kooperationen – speziell auch in selbstorganisierten Zusammenhängen – prägen den Alltag einer KünstlerInnengeneration, für die die ständige Verfügbarkeit ortsunabhängiger Information ebenso Normalzustand wurde wie die Vertrautheit mit den Apparaturen ihrer Aufzeichnung und Vermittlung.

Annja Krautgasser fand in ihren Arbeiten zu einem überzeugenden Umgang mit jenen Spannungsverhältnissen. Möglicherweise half ihr dabei ihre Ausbildung zur Architektin und der Umstand, dass ihre künstlerische Beschäftigung näher am virtuellen Raum begann,

was etwa ein Blick auf die Arbeit IP-III (2003) zeigt, deren „Raum“ durch die Übersetzung von IP-Adressen in abstrakt-räumliche Koordinaten entstand. Trotz ihrer puristisch medien-

inhärenten Logik beinhaltet die Arbeit grundlegende Parameter von Krautgassers Heran-

gehensweise an reale Orte, insbesondere eine – an Abstraktion und Mustern geschulte – Sehweise mit starker Verankerung in der abstrakten Kunst des frühen 20. Jahrhunderts. Folgerichtig legt die Künstlerin Wert darauf, sich von einer apparativ-technoiden „Medien-kunst“ abzugrenzen und ihre „Verortung“ in darüber hinausgehenden künstlerischen Langzeitentwicklungen zu betonen.

Ein zeitgemäßes Verständnis von Ortsbezug kann darin bestehen, jene Verfahren zu überwinden, die darauf abzielen, dem „Einzigartigen“ nachzuspüren, und stattdessen ein künstlerisches Instrumentarium zu entwickeln, mit dem örtliche Realitäten in einen übergeordneten Zusammenhang gebracht werden können. Diese Form einer gewissen Abstraktion des Lokalen ist Voraussetzung dafür, die eigene Kunstpraxis in überörtliche und längerfristige Entwicklungen einbetten zu können, ohne auf konkrete örtlich-räumlich-soziale Beziehungspotenziale verzichten zu müssen. Wenn also Annja Krautgasser etwa

in ihrer Arbeit Dashed II (2006) zwölf Personen weltweit nach Raumerinnerungen und

Raumbeschreibungen befragt und diese Erzählungen auf die Bildschirme von Mobiltele-fonen überträgt, liegt der Erkenntnisgewinn gerade darin, in welch präziser Form die Erzählungen der Befragten an konkrete Orte und Räume gebunden bleiben, obwohl zu-gleich Form und Format der Vermittlung (englische Sprache, visuelle Vereinheitlichung) dafür sorgen, das Allgemeingültige und Verbindende der Erzählungen herauszustreichen. In diesem Falle führt die Formalisierung der konkreten Erfahrungen der ProtagonistInnen dazu, dass sich aus den intimen Erinnerungen mehr und mehr die Beschreibung räumlicher Urtypen (Kinderzimmer, leerer Saal, Club, Auto u. Ä.) als jenes Element herausschält, das den Kern der Arbeit bildet.

Annja Krautgassers Methode bringt es mit sich, dass die Werke jeweils in zwei Richtungen „funktionieren“. Eine Rezeptionsbewegung führt näher an das Spezifische heran, während ein anderer Weg zu Mustern und Strukturen weist, die überindividuelle Kommunikation ermöglichen und deren visuelle Qualitäten das Andocken an kunstimmanente Diskurse ermöglichen. Krautgasser verharrt formal oft „halfway“, wie z. B. mit dem gezielten Einsatz

von Unschärfe in einer Serie von Arbeiten, die Bewegungen im Raum zum Inhalt haben. So bewegen sich in Horizon/1 (2005) und Around and Around (2007) immer wieder schemenhafte Landschafts- oder Stadtraumelemente durch das Bild. Diese roadmovie-gleichen Sequenzen, welche in Zeitlupe und Vergrößerung wohl identifizierbar wären, entfalten jedoch eher als traumhafte Muster ihren Sog. Oft unterstützen minimalistisch-technoide Soundtracks wie der des italienischen Duos TU M’ in Horizon/1 diese ambiva-lenten Erfahrungsmöglichkeiten. Auch Zandvoort (2009), eine in einen 13-minütigen Film kondensierte Tagesbeobachtung eines niederländischen Strandes aus einer fixierten Kameraperspektive, konterkariert die titelgebende örtliche Konkretheit durch einen distanziert-erhöhten Blickwinkel und subtile Bildmanipulationen. Aus dem Strand wird das Muster eines Strandes, und der kunsthistorische Anschluss gelingt in diesem Fall durch eine an Caspar David Friedrich oder William Turner erinnernde Motivwahl. In diesen Arbeiten gelingt Annja Krautgasser ein Oszillieren, dem neben formaler Souveränität auch ein Potenzial zu Verunsicherung und Suspense eigen ist, da sie ihre Quellen und Referenzen – wenn überhaupt – erst in den Credits oder in begleitenden Texten eröffnet. Die Künstlerin erzeugt somit eine vage Grundspannung, die jäh ins Konkrete kippen kann, etwa wenn die Töne von Blindenampeln, installiert in einem Wiener NS-Bau, sich mit der Erinnerung an Klopfzeichen als Gefängniskommunikation und beim Bau beschäftigte Zwangsarbeiter kreuzen (What Is My Position, 2004). |

|

|

| Beschreibung - E (description english) |

| There are actually two versions of the latest video by Annja Krautgasser (aka [n:ja]): One is called Innerer Monolog (Stream of Consciousness), the other is called Beyond. Even though, except for the closing scenes, Krautgasser has used almost the same footage for both videos the two works are very different. Whereas in Innerer Monolog she focuses on an architectural portrait of a building in the 15th district of Vienna, which has a soundtrack that adds rich atmosphere by means of imaginary episodes, in Beyond, the visual perspective is extended by another level: the artist shows the (unexpectedly large) film set in the last shot to reveal the way the video was made. She illustrates the method and conditions of the production in exactly the same way as she did with several fragments of the architectural composition that came before. Only the bright flashing light of varying intensity that is created by a welding torch opens and closes the view of the building’s façade, and also of the recording equipment being used. The architecture—appropriately, a transformer station—flickers to the rhythm of the work in progress. The video proves to be a structurally designed architectural portrait as well as a making-of film.

Technically, Beyond consists of three movements that flow into one another and are regularly interrupted by black frames—complete darkness. The camera pans from left to right past individual details of the modern looking frontage before panning back to show a view of the façade—subsequently repeatedly, but nevertheless remaining fragmentary. From the middle of the work onwards the camera movement reverses until, with a light pan upwards, the shot of the frontage sinks into the darkness of the night. Krautgasser plays here with the conventions of the genre. Following the logic of suspense, only a trace or slightly too little is to be seen, while on the level of the soundtrack—passing cars, clacking high-heels, bird twittering—everything remains only suggested. Incidentally, the building does not yet feature anywhere in the official history of Austrian architecture. Constructed by the architect Heinrich Schmid in the 1970s, this building—like the videoBeyond—leads a discrete existence.

(Dietmar Schwärzler)

Safe Navigation

Site Specifity and Space in the Works of Annja Krautgasser

Martin Fritz

Artists have to develop relationships to the locations of their work. The issue of the artwork’s relationship to the place of its production arises whether this is in the studio, travelling, or within the institutions. This relationship, which appeared to have become irrelevant through the various detachments of art from the depiction of its setting until, at the latest since the 1960s, was brought up to date as the formal demand of site-specifty and the social potential of context-orientation. Additional topicality was developed by the issues addressed in connection with the mobility that artistic activity demanded of its participants, i.e. that geographic spatial mobility which enabled them to act from a multi-perspectival standpoint. Numerous residencies, grants bound to travel and transnational cooperations—especially also in a context of self-organisation—characterise the everyday lives of a generation of artists for whom the continual availability of information not bound to any specific location became as normal as did familiarity with the apparatus of its docu-mentation and mediation.

Annja Krautgasser has found a way to handle these charged interrelationships convincingly in her work. Her training as an architect has possibly been of help here, as is the fact that as an artist she began by engaging more closely with virtual space, as shown in the work IP-III (2003), whose “space” was the product of the translation of IP addresses into abstract spatial coordinates. Despite the purist logic inherent to the media, the work contains the basic parameters of Krautgasser’s approach to existing locations, and in particular a way of looking—trained on abstraction and patterns—with a strong anchor in the abstract art of the early 20th century. Accordingly, the artist places value on distancing herself from an apparatus-dominated technoid “media art” emphasising her position in a long-term artistic development that goes beyond it.

A contemporary understanding of site-specifity can consist in overcoming those processes geared to tracing what is unique and instead developing artistic instruments with which the given realities of the location can be introduced into a broader context. This form of a kind of abstraction of the local is the prerequisite for embedding an artist’s practise in supra-local and longer-term developments without having to relinquish the potential for concrete local, spatial, and social relationships. When, then, Annja Krautgasser asks twelve people around the world about their memories of a space and for their descriptions, in

the work Dashed II (2005), and then plays their responses back on the screens of mobile

phones, the conclusion lies in the precision with which the interviewees’ accounts remain

tied to concrete spaces and rooms. This, even though the form and format of the communication (in English, and with visual uniformity) emphasise the universally applicable and binding in the narratives. In this case, the formalisation of the protagonists’ concrete experiences leads personal memories to increasingly become descriptions of basic types of room (a playroom, an empty hall, a club, a car, etc.) as the element that emerges as forming the core of the work.

Annja Krautgasser’s method allows the works to “function” in two different directions. One direction in the reception leads to what is specific, while a second direction leads to patterns and structures that permit supra-individual communication and whose visual qualities allow them to dock onto current art discourses. Krautgasser frequently insists on stopping halfway, for example, with the careful use of blurred focus in a series of works that engage with movements in space. Accordingly, in Horizon/1 (2005) and Around and Around (2007) schematic landscapes or elements of urban space repeatedly move through the image. These Road Movie-like sequences, which would be identifiable played in slow motion and enlarged, develop their draw, though, as dream-like patterns. These ambivalent experiential possibilities are frequently underpinned by minimal techno soundtracks, such as the one by the Italian duo TU M’ for Horizon/1. So too, Zandvoort (2009), where observations, made during a day on a Dutch beach, are shown condensed into a 13-minute film from a fixed camera angle and counter the specificity of the location named in the title by an “impersonal” raised camera angle and subtle manipulation of the image. The beach becomes the pattern of a beach, and an art historical allusion is achieved with a choice of motif reminiscent of Caspar David Friedrich or William Turner. In these works she achieves an oscillation that has, alongside formal sovereignty, an intrinsic potential for uncertainty and suspense as her sources and references are not revealed until the credits or the accompanying texts—if at all. Like this, the artist generates a vague basic tension that can abruptly tip concretely, for instance when the sounds of signals for the blind, installed in a Viennese NAZI building, overlaps with the memory of knocking signals as prison communication and forced labourers occupied on building sites (What Is My Position, 2004).

Precisely the example of this gain in significance—provided by the specific history of the installation’s venue—shows that site specifity encompasses far more than a reaction to obvious architectural features of the space. Spaces are information bearers—and urban spaces are in particular. Their surfaces and symbols allude to history and narratives. Logos and other signals lead from the buildings to the information and, at the same time, the information media command ever-improving possibilities for the representation of spatial architectural qualities. The transitions between the real spaces and their medial representation become more liquid, which in turn leads to a boom in the range of site-specific information and the tools required. Paradoxically, prerequisite for the use of these tools in a mobile everyday life are standardisation and a universally applicable form as only familiar patterns that facilitate recognition and orientation. Annja Krautgasser is capable of using this situation well, as systems of organisation and their three-dimensional realisation have long been the basis of her practice. Accordingly, she increasingly frequently combines filmic or medial space with sculptural and installative solutions that aim to restore something physical and tangible to the ephemeral nature of the topics she addresses. This and her skill with formal reduction, in combination with the orientation on patterns and principles mentioned above, contribute to maintaining the legibility beyond the relevant context of production for those of her works that are bound to given locations and specific research. Road maps of Los Angeles become Perspex sculptures, and so convey general thoughts on orientation, memory, and space (Remember Me, 2005); poor screenshots from online sources are painstakingly translated back into aerial photographs—enhanced to become a high-end photographic work—and supplement the artist’s real topographical experiences of cruising (Perceiving L.A. Within 109 Days, 2006).

A further approach taken by Annja Krautgasser to engaging with the multiplicity of meaning of space and visual patterns lies in the production of different versions of the same work, and so in the associated extension of the possible allusions. This approach, too, permits her to engage with the relevant material both concretely, i.e. locally, as well as abstractly and so supralocally. Accordingly, her filmic excursion past the ornamented façade of an abandoned electricity works building exists in two versions: while in one version the pattern on the façade is shown almost exclusively in close-up and so isol-

ated from its context (Innerer Monolog, 2008), the second version opens the view at the end to show a “making of” of the film—and so the local conditions of its production (Beyond, 2008).

The artist took a similar approach, albeit with stronger narrative potential, to her research into a number of neighbouring building complexes in Amsterdam that had been used

by the major newspapers until recently. An almost documentary-style video opens the space up to the viewer with only isolated signs of its former use to be seen. Similarly, the continued existence of the logos stands for a very specific local media history. This is a history that Krautgasser initially shows in generalised terms with a view of the empty spaces, and follows with the historical context of the actual location in the end credits.

So when she subsequently has a reconstruction of the (newspaper’s) logo made in Vienna, this sculpturalisation not only allows the topic to be transported outside its original context but also to be addressed in a more general manner—without which its reception would be hampered outside of the Netherlands (Trouw, and What Remains, 2009).

These and other—more recent—works show an extension of Krautgasser’s range, and again she brings apparent opposites into a productive balance: while on the one side of her development is an increased awareness of social processes and their formal organisation, she increasingly selects installative and object-orientated strategies to do justice to the heterogeneity of her subject matter. This, too, accords with a contemporary notion of site specifity: in the foreground is not a visual power game with locations and places, their proportions and volumes, but the attempt to do justice to the places’ history, and transfer existing references into suitable formats. In the final analysis, it is Annja Krautgasser’s sovereign treatment of the most varied of formats where the core of contemporary artistic competence is to be seen: navigating safely through the complexity of multiple references and allusions. |

|

|